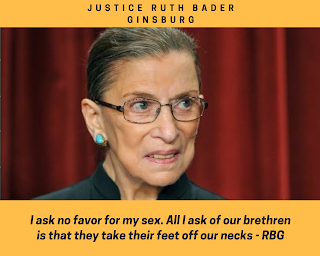

In 1956, 23-year old Ruth Bader Ginsburg,

fondly called ‘Notorious RBG’, got her admission in Harvard Law School. She was

one among the nine woman - in a class strength of 500. Her dean invited all nine

women law students home for dinner, and asked each one of them what they were

doing taking the place of a man. The fact that this could happen in the country

with the oldest written Constitution of the world, and in one of the world’s

most prestigious law schools, reflects how deeply embedded gender bias has

always been.

Around 4 years later, just as RBG finished

law school with good grades, another Dean at Harvard recommended her for a

clerkship with Justice Felix Frankfurter of the US Supreme Court. Justice

Frankfurter refused to hire her, stating that although her candidature was

impressive, he was still ‘not ready’ to hire a woman. RBG could also not find a

job in any law firm in New York, as all of them refused to hire a woman. But,

none of this deterred her, and only strengthened her resolve to fight against

gender-based discrimination.

From 1963-1972, RBG spent the early years

of her career as a Professor in Rutgers Law School, where she taught courses on

civil procedure and ‘gender and law’. In 1971, RBG wrote her first brief for

the US Supreme Court in Reed v. Reed.

In Reed v. Reed, the issue was whether a State could directly prefer men

over women as executors of family property. The US Supreme Court answered in

the negative, and struck down the State law on the ground that it violated the

equal protection clause, present in the 14th Amendment

of the US Constitution. This was the first time that the US Supreme Court had

struck down a State law for being gender discriminatory.

RBG firmly believed that the equal

protection clause should invalidate any law that was gender discriminatory. While

this interpretation may seem obvious today, RBG says that she had faced a tough

challenge in convincing the Court - as many judges did not even believe that

there was something known as gender-based discrimination! She had to tap into

the emotions of the judge, and would ask them about the kind of world they wanted

to leave behind for their daughters and granddaughters.

She argued her first case before the US Supreme Court in 1973, where she represented Sharron Frontiero - an Air Force employee who had been denied housing allowance because she was a woman. RBG was among the first to convince the Court that along with affecting woman, gender discrimination of any kind also affects society at large. This was a point she stressed on while representing Steven Wiesenfield, who was denied social security benefits after losing his wife as soon as she gave birth to their child.

Steven was denied social security benefits on the ground that only widows were eligible to receive it, and not widowers like him. Before the Supreme Court, RBG argued that denying social security payments to a man was based on the stereotype that only women can be homemakers - for taking care of their children. This case epitomized her approach, where she focused on gender discrimination from a perspective of social consequences, and not solely as a man-woman binary.

After her stellar work for gender

justice, she was nominated as a Federal Judge in the Columbia Circuit, where

she served for 13 years before being nominated to the US Supreme Court in 1993,

at the ripe age of 60. RBG was just 1 out of almost 30 candidates who were shortlisted

for elevation. But, when she was called to the White House for an interview

with President Bill Clinton, it took her just 15 minutes to convince him about

what she could bring to the table – as the 2nd woman to be appointed

to the Supreme Court.

In her 27 years in the Supreme Court, RBG’s

judgments reflected the changes that she wanted, and had always fought for. She

struck down the

admission policy of the Virginia Military Institute, which forbade women from

applying for admission even if they were capable of satisfying the admission

criteria. Although inducting women faced resistance at multiple levels, RBG stuck

to her view of the equal protection clause, stating that if women were given

equal opportunity, even they can do us proud.

RBG also penned a number of landmark

dissents, where she hoped that her views would “appeal to the intelligence

of a future day”. She dissented from the majority view in the Ledbetter case

- where the majority refused to honour Lilly Ledbetter’s right to receive equal

pay in comparison to her male counterparts. While upholding Ledbetter’s right

to receive equal way, she called out the majority judges’ indifference towards

the different ways in which gender-based wage discrimination can take place.

She concluded her dissent by stating

that now, “the ball is in Congress’ Court”. This definitely appealed to the

intelligence of a future day, as two years later, the US Congress passed the

Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act, 2009.

During her tenure in the Supreme Court, RBG also developed a close friendship with Justice Scalia, even though he was a conservative, and disagreed with her at an ideological level. Their opposite ideological viewpoints and disagreements on the Bench did not affect their personal equations. In fact, Justice Scalia had once jokingly remarked that the only thing he didn’t like about RBG was her reading of the law! Their friendship is a lesson for everyone in these polarized times, where we tend to hamper our personal equations with those who disagree with us ideologically.

From being denied clerkships and law firm jobs on account of her gender, RBG charted her own journey - by providing a new name to gender justice. Her vision of creating a better world for our daughters and granddaughters must be cherished, preserved and fought for. RIP.

No comments:

Post a Comment