(This post takes you through the story behind Indira Gandhi's bank nationalization decision, and the litigation that followed)

19th

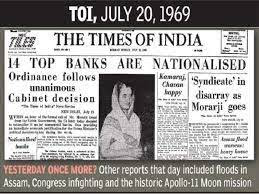

July marked exactly 51 years since Indira Gandhi’s bank nationalization ordinance. Indira Gandhi’s decision to nationalize 14 commercial banks was brought about on 19th July 1969, which was a Saturday. Nationalizing 14 commercial

banks through this ordinance brought more than 75% of India’s banking sector

under direct State control. All assets, liabilities and paid-up capital of the

14 commercial banks were to vest directly with the Central Government. The

ordinance was promulgated on a Saturday even though Parliament was scheduled to

reconvene on Monday, 21st July 1969 – which was less than 48 hours

away.

The ordinance

was also drafted in utmost secrecy. Only Indira Gandhi’s trusted officers were

aware about the plan, and even the Cabinet Ministers were not kept in the loop.

As Granville Austin notes in his book - Working a Democratic Constitution,

Indira Gandhi’s Cabinet colleagues heard about the ordinance only once they

arrived at the Cabinet Meeting, which was called to give rubber-stamp approval

to the ordinance.[1]

Even copies of the ordinance that had been circulated during the meeting were

taken back, so that there were no leaks in advance.

After the

Cabinet Meeting, the ordinance was taken to Acting President V.V. Giri for his

assent. Interestingly, V.V. Giri, who was then the Acting President after the

death of President Zakir Hussain, was going

to demit office the next day. This was because he was contesting as a

candidate in the upcoming Presidential elections.

Indira

Gandhi announced her decision to the public through a radio broadcast in the

evening. She stated that this decision was necessary for a larger social purpose,

and was done to make banking facilities more accessible in rural areas. This

was the first among many measures that Indira Gandhi undertook to facilitate

greater State control over different sectors of the economy.

The

events of 19th July 1969 have an eerie resemblance with 8th

November 2016, when Narendra Modi shocked us all by announcing demonetization through

a televised address. Akin to the bank nationalization decision, Modi’s Cabinet

Ministers were

informed about demonetization only in the Cabinet meeting that took place

before the announcement. In fact, to prevent any leakage of information, the

Cabinet Ministers were also prevented from bringing in their cellphones, and were

not allowed to leave the meeting venue until Modi ended his television

speech!

Be that

as it may, there is one other common factor between demonetization and bank

nationalization. Both were undertaken keeping in mind political considerations,

along with other economic and social factors. In Indira Gandhi’s case, bank nationalization

was a move that would establish her supremacy within the Congress, and prevent challengers

like Morarji Desai from taking control of her party or Government. It is for

precisely this reason that Morarji Desai was sacked as Finance Minister on 17th

July, which was two days prior to the promulgation of the bank nationalization ordinance.

The bank

nationalization ordinance was severely criticized by other smaller political parties

like the Swatantra Party and the Jan Sangh. They argued that bringing more than

three-fourths of the banking sector under direct State control would cripple its

growth in the long-run, and shall also lead to losses, corruption and red-tapism.

While this was debated, preparations were already underway for challenging the

ordinance before the Supreme Court. On Sunday, 20th July 1969 (one

day after the ordinance was promulgated), the legendary Nani Palkhivala took a flight

to Delhi.

As Soli

Sorabjee and Arvind Datar write in Nani Palkhivala: The Courtroom Genius,

the writ petition to challenge the ordinance was drafted and finalized by Palkhivala

a few hours after his arrival.[2]

It was filed in the Supreme Court on Monday, 21st July 1969, which

was less than 48 hours after the ordinance had been promulgated. The petitioner

before the Supreme Court was Rustom Cavasjee Cooper.

R.C. Cooper

was a Director and shareholder in the Central Bank of India. He was also a

shareholder in Bank of Baroda and Bank of India Ltd. All of these 3 banks had

been nationalized under the ordinance. The Supreme Court granted an interim

order on Tuesday, 22nd July, and restrained the Government from removing

the Chairmen of all the banks which had been nationalized.

As the

Supreme Court was seized of this petition, the ordinance was replaced by the Banking

Companies (Acquisition and Transfer of Undertakings) Act, 1969 (‘the Nationalization

Act’) - which was passed in Parliament on 8th August. The

Supreme Court subsequently began hearing arguments on the unconstitutionality

of the Nationalization Act, and the ordinance which preceded it. While

Palkhivala advanced several arguments, let us briefly discuss two of his main

arguments. Palkhivala first contended that the compensation that was being paid

to erstwhile shareholders of the 14 banks was severely inadequate.

He argued

that this was in violation of Article 31, under which the State had an

obligation to pay full and adequate compensation while acquiring property. He

also contended that the Nationalization Act violated Article 19(1)(f), which

had conferred the right to acquire, hold and dispose off property. (Both

Article 31 and 19(1)(f) were subsequently repealed through the 44th

Amendment in 1978).

Palkhivala’s

other key argument was based on Article 14, where he contended that there was

hostile discrimination against these 14 banks - as they were prevented from carrying

on banking business after being nationalized. He argued that other banks which

had not been nationalized were not subjected to this disqualification, and even

foreign banks were allowed to carry on banking business.

After

hearing arguments, the Court delivered its verdict on 10th February 1970,

which was less than 7 months after Indira Gandhi’s decision to promulgate an

ordinance on a Saturday.[3]

The majority opinion was delivered by Justice J.C. Shah. While Justice Shah upheld

Parliament’s legislative power to nationalize banks as a whole, he concluded

that the Nationalization Act failed to pass constitutional scrutiny.

He accepted

Palkhivala’s argument on violation of Article 14, 19(1)(f) and 31. Significantly,

the Court also overruled two principles laid down in A.K. Gopalan v. State of Madras

(1950). In A.K. Gopalan, the majority led by Chief Justice Kania

held that each fundamental right was mutually exclusive, and had to be looked

at independently from other fundamental rights.

The

majority also held that while determining whether a law violated any fundamental

right under Part III of the Constitution, the Court would have to examine the

object of the law, and not the effect that the law has on fundamental rights. Justice

Fazal Ali did not agree with the majority, and took the view that every fundamental

right is not a separate compartment, and that all fundamental rights are

mutually interdependent. Justice Fazal Ali’s dissenting view was upheld 20 years

later by the majority in R.C. Cooper.

The

majority in R.C. Cooper overruled Chief Justice Kania’s view and conclusively held

that fundamental rights were mutually interdependent, and not mutually exclusive.

In other words, a law that was challenged as violative of 31 could also be

violative of Article 19(1)(f), or Article 14, as none of these rights should be

looked at as isolated compartments.

The majority

also held that while examining whether a law violates fundamental rights, the

Court shall have to scrutinize the effect that the law has on fundamental

rights, and not the object that the State sought to achieve. Hence, two aspects

of the Chief Justice Kania’s decision in A.K. Gopalan were overruled 20 years later,

and the fundamental rights chapter was made permanently stronger.

This judgment

laid down the foundation stone for Justice Bhagwati’s opinion in Maneka Gandhi v. Union of India,

where it was held that Article 14,19 and

21 formed a golden trinity, and that any law which is challenged under Article

21 should also meet the tests reasonableness under Article 14 and 19. This also paved the way for reading in unenumerated rights into Part III, such as the right to privacy and the right to food. Justice

Fazal Ali’s dissent hence became the starting point for a more progressive

interpretation of the fundamental rights chapter.

The

decision in R.C. Cooper was however not unanimous. Justice A.N. Ray

dissented from the majority and upheld the Nationalization Act. Ironically,

three years later, Justice A.N. Ray was appointed as the Chief Justice of India

by superseding Justices Shelat, Grover and Hegde, who were above him in the

order of seniority. This was after Justice Ray held in favor of the Government

in the Keshavananda Bharati case, and was the first instance where senior

judges were superseded for the post of Chief Justice of India.

Following

the decision in R.C. Cooper, the Central Government was forced to pass a

fresh bank

nationalization legislation in Parliament. This acquisition of the ownership

of 14 banks has not been undone until today, despite severe criticism of the

corruption and inefficiency that plagues the public sector banking system. Even

the Modi Government does not seem to have any plan to undo all of the changes

brought about in 1969, despite enjoying a majority in Parliament. Bank

nationalization has hence effectively acquired a level of permanence in our economic

polity.

Another significant

aspect to note here is the duration within which this judgment was delivered –

which was less than seven months after Indira Gandhi decided to take the

ordinance route. This can be contrasted with the situation we have in the

Supreme Court as of today. The petitions challenging the constitutionality of

the Citizenship Amendment Act, which was passed in December 2019, has not even

been listed for a hearing. Even the challenge to the Article 370 amendment and

the Jammu & Kashmir Reorganization Act, 2019 has met a similar fate, almost

one year after they were passed in Parliament on 5th August 2019.

While R.C.

Cooper’s overruling of A.K. Gopalan still forms the pillar of our

fundamental rights chapter, the speed and alacrity with which significant constitutional

cases must be heard and adjudicated is another takeaway that we should remember.

[1] Granville Austin, Working a Democratic

Constitution: A History of the Indian Experience, Pg. 215.

[2] Soli Sorabjee and Arvind Datar, Nani Palkhivala:

The Courtroom Genius, Pg.60.

[3] The then Chief Justice of India, M Hidayatullah,

could not be a part of the Bench as he was sworn in as the Acting President of

India on 20th July 1969. This was after V.V Giri demitted office as Acting

President - to contest as a candidate in the upcoming Presidential elections.

No comments:

Post a Comment